The fourth of seven children of illiterate parents, Mohammad Ahmad grew up on his family's two-acre farm with barely enough to eat. Now that farm, which supports two dozen people in his extended family, is being used as collateral for a chance to score big here in India's cram school capital.

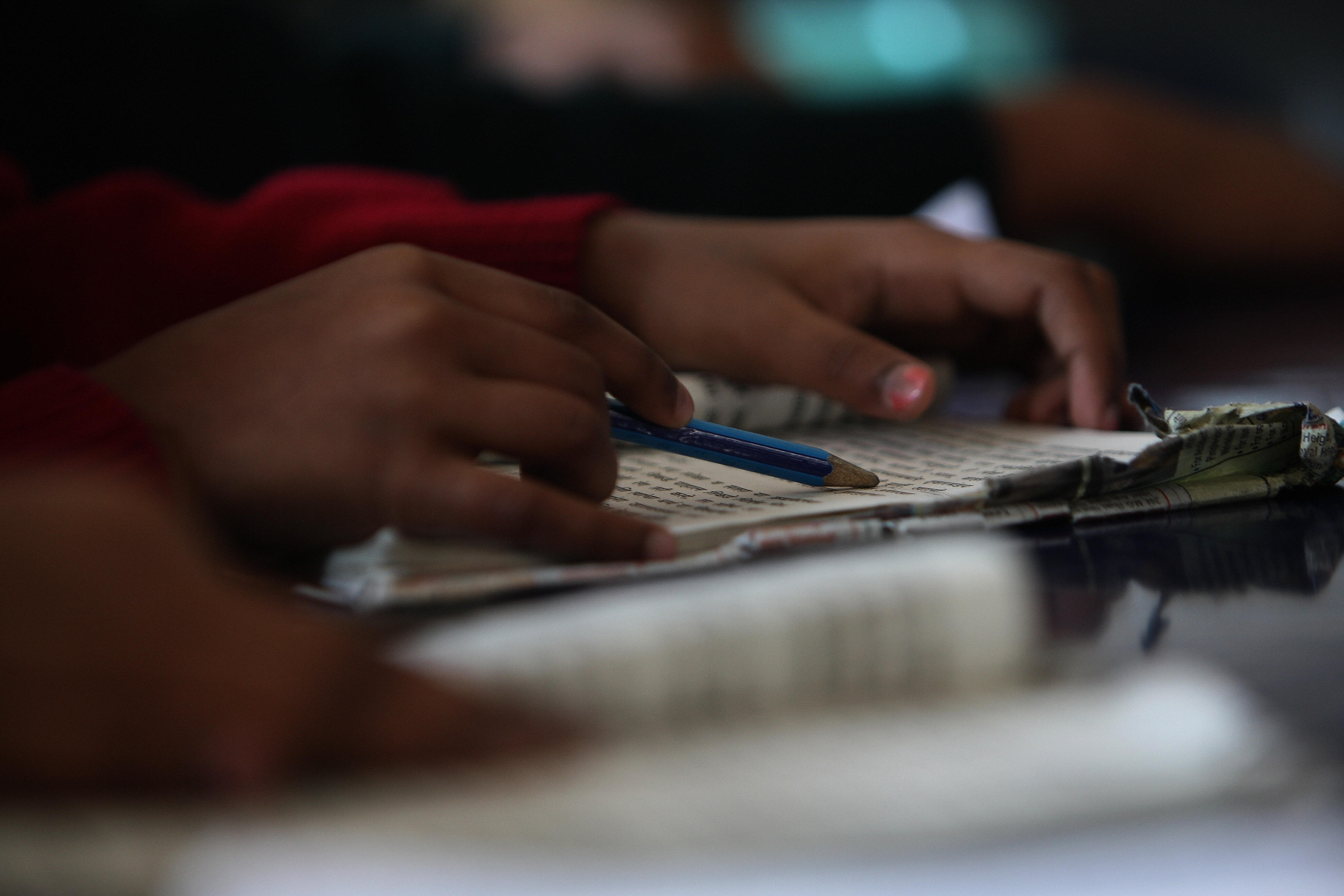

For up to 19 hours a day, seven days a week, the 17-year-old studies, attends classes and takes mock tests, preparing for India's ultra-competitive engineering entrance exam.

In this second-tier city of dusty storefronts and belching rickshaws, Ahmad and the tens of thousands of other students embody a nation's hunger for upward mobility, social respect and a role in the new India. One can almost hear the angst in the creak of cheap student bicycles and the mantra of parents: Forget exercise, dating, video games. How will you ever get into engineering school if you don't study more?

The Holy Grail is a spot at one of 15 Indian Institutes of Technology, or IITs. Admission is blisteringly difficult -- think Harvard, Princeton and MIT combined. This year, half a million test takers nationwide elbowed for 9,647 spots. As CBS' "60 Minutes" said, the IITs are "the most important university you've never heard of."

Driving India's love affair with the schools is the promise of higher income, social status, even marriage prospects. Graduates command high salaries, better dowry terms and promising job offers with top Indian and multinational companies. Although many don't ultimately go into engineering, an IIT degree can open doors.

But the entrance exam's 98% failure rate can destroy the dreams of families such as Ahmad's that can ill afford the fees, which approach $1,400 annually.

"This isn't competition, it's gambling," said Abdul Mabood, director of the national help line Snehi, which counsels stressed students, including the legions who travel to this northern city where billboards aplenty promise success: "Unbeatable Performance!" says one. "Bull's Eye Classes," reads another.

Kota's emergence as cram capital for the 4 1/2-hour annual IIT entrance exam owes much to serendipity.

In the mid-1980s, mechanical engineer V.K. Bansal received a diagnosis of muscular dystrophy, quit his job and started coaching IIT aspirants in his kitchen. A few years later, fellow IIT graduate Pramod Maheshwari abandoned dreams of living in the U.S. after protests from his mother and started coaching from his garage.

Both saw their students do well -- IIT admissions are so celebrated that top entrants are front-page news -- and word spread. In 2000, a Bansal student garnered the highest score in India. "It was a gold medal for us," said A.K. Tiwari, Bansal's chief technology officer in a company that now has 17,000 students and dozens of teachers and administrators.

Both Bansal and Maheshwari are now multimillionaires running massive competing schools. In fact, once-industrial Kota boasts 129 "coaching institutes," from holes in the wall to marble-gilded learning factories.

"I haven't seen a single parent say they don't have the money -- they'll sell land, borrow, anything," said Prakash Joy, president of Ables Educations, another Kota cram school.

Spots at the top cram schools are so coveted that entrants take tests to join, even as schools compete to retain top instructors for programs ranging from four months to two years. "Poaching comes with coaching," said Maheshwari, whose Career Point institute boasts 20,000 of Kota's estimated 100,000 students.

For anxious parents, a key attraction to Kota is its near-complete lack of multiplex theaters or pubs. "I have no friends here," said Surabhi Kumari, 17, at Career Point. "My father doesn't want me using my phone. I'm here to study."

Local families in conservative Kota, traditionally known for its woven saris and Mughal military legacy, also play their part. While renting out rooms to students, many serve as surrogate parents, keeping careful watch over their young tenants, tracking their whereabouts and discouraging horseplay.

Four years ago, the city opened its first mall, but most students are so focused they don't know where it is, said Sumit Chaturvedi, 32, who runs hostels for boys and girls. (Separate, of course.) Recently, Chaturvedi evicted a boy for smoking so he wouldn't influence others.

"We keep these things in mind," he said. "Kota is much better for studying. Most big cities have lots of entertainment and distractions."

The IITs are the pride of India, largely free of politics or corruption, earning kudos in 2003 from Microsoft's Bill Gates for helping build Silicon Valley. Indeed, the cram schools and IITs have been criticized for subsidizing brain drain. An old joke holds that IIT graduates have one foot in India, the other aboard Air India.

Others question whether success comes at the cost of creative thinking.

"This has become an exercise much more in memorization rather than helping independent thinking," said N.R. Narayana Murthy, founder of high-tech pioneer Infosys, who says 80% of IIT graduates leave much to be desired.

The grueling process carries another price. "People who miss passing by one-tenth of a percent think they're failures," said Shiv Visvanathan, a sociology professor at O.P. Jindal Global University in Sonipat. "It's mass production of engineers, many of whom don't want to be engineers. The dream has become a nightmare."

Some of the ambivalence was captured in the 2009 Bollywood blockbuster "Three Idiots," about three engineering students, only one of whom enjoys engineering. "I will curse you the rest of my life if you force me" to become an engineer, one character tells his father. "Please, let me do what I want."

Coaching institutes deny they foster an over-reliance on rote and argue that the IITs are a means to an end. Only 20% to 25% "of people end up in engineering," said Career Point founder Maheshwari. "But you essentially go through a process and become logical and creative."

Tiwari, Bansal's technology head, pops into classrooms on an overcast afternoon where as many as 140 students at narrow desks watch teachers solve problems on overhead projectors. "If the government schools were doing their jobs, there'd be no need for coaching," he said.

Although Ahmad's family is very poor, his brother Nizamuddin, 28, a doctor's assistant, wanted him to dream big. When other family members balked at Kota's steep fees, the brother lobbied relentlessly, helping secure a $1,100 loan backed by the farm.

"He's been like a father to me, hellbent on finding a way for me to study," Ahmad said. "I owe him everything."

Even so, Ahmad arrived in Kota $950 short for the two-year cram course. Administrators denigrated him for being poor, Ahmad said, urging him to quit and barring him from classes. But his brother eventually scrounged together most of the shortfall.

Ahmad says his studying is coming along, although living in Kota is expensive. "The rich students spend money like water," he said. "Some laugh at me for being poor, but I ignore them."

Rising at 5 a.m., he studies chemistry and physics until noon, takes classes all afternoon, then studies until midnight, knowing how much depends on his results. He dreams of getting a good job, buying a laptop and supporting his parents.

"For engineers, the sky is the limit," he said. "It's a risk, but I'd never forgive myself for staying in the village and never trying."

mark.magnier@latimes.com